A.L.C. Atkinson’s Russian Adventure

A.L.C. Atkinson’s Russian Adventure

In Feb. 1909, Elk A. L. C. “Jack” Atkinson was appointed U.S. District Attorney. The press, and maybe Jack, thought a new career had begun, but before the year ended, Atkinson was distracted by adventure in Russia. Not revolution nor gold, not vodka nor caviar, but the need for labor on sugar plantations took Jack to Russia.

In 1909 Atkinson, then Secretary of the Territorial Board of Immigration, took on adventure and ended up at the center of an immigration experiment “lost in translation.”

The Board of Immigration managed immigration of low wage agricultural workers. The worldwide labor search for people willing, and permitted, to leave home searching for a better life traditionally had led to China and Japan.

Two years after Annexation, Federal and Territorial agreement was reached on governing Hawaii under US laws. The resulting legislation subjected Hawaii to Federal immigration law including the Chinese Exclusion Act. Federal laws also voided many provisions in standing Hawaii plantation labor contracts holding works to plantation jobs for a pre-determined period. Plantation owners remained in control, but workers could and did leave plantations. Quickly small strikes tested leverage in wage and working demands.

1907 Federal US legislation and the “Gentleman’s Agreement” (Japan agreed to unilaterally restrict passports, thus restricting travel to the US), further reduced the labor pool for Hawaii plantations. With no political leverage (no vote in Congress), Hawaii planters received could not obtain an agricultural waiver. The plantations experiments with Korea and Portugal as new labor sources. In 1907, workers came from Spain, but few stayed in Hawaii.

In May 1909 on Oahu, 5000 Japanese plantation workers went out on strike. Owners tried to break the strike in many ways, even evicting families from housing. Planters’ long-term ‘solution’ was to add Philippine workers, diluting Japanese labor dominance. A fast-fix was needed making the Sugar Planters Association ripe for schemers.

Into the storm came A. V. Perelestrous, promising to deliver Russian workers used to hard work. Perelestrous would recruit these laborers in a political gray zone: Harbin, Manchuria, on the Siberian border. ‘Hold on, workers will come’ plantation managers were told.

Perelestrous left Honolulu hunting workers, followed in Aug 1909 by Immigration Board Secretary, Atkinson. Manchuria was a wild frontier: Atkinson hired 2 body guards, and carried a “Colt’s revolver.” He was ill-equipped to explain plantation labor to Russians, with a vocabulary of da (yes) and net (no). Jack and the Planters trusted Perelestrous’ translation from English into Russian of the cost of living, employment terms, benefits, and the possibilities of future American citizenship. The printed terms offered recruits a paradise with little resemblance to real plantation conditions. For example, some immigrants later stated they believed they could expect to homestead and eventually own the land they would work.

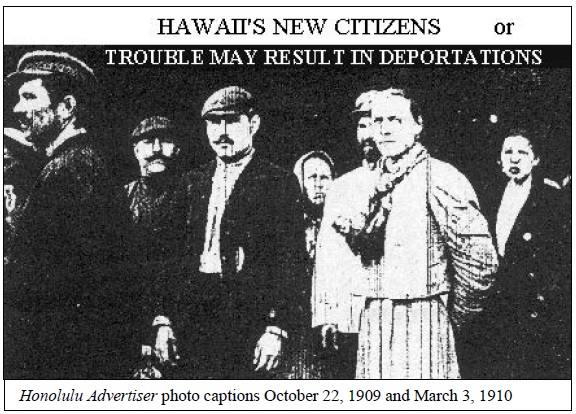

Oct 21, 1909: the first Russians arrive in Honolulu and the Honolulu Advertiser reporting glows with headlines like “Splendid people respond to invitation.” A photo of the immigrants is titled “Hawaii’s New Citizens.” Readers are reassured the newcomers are good additions to the community: “All Family Groups,” “Want no Priests.” The Planters’ dreams had come true: “Cheaper than Coolies,” “No Promises Made.” Readers learn of a troublemaker shipped home, a potential problem squelched in “One Anarchist.”

Perelestrous was eager for more work: “I can bring to Hawaii not 10,000, but 100,000…the only limit is the amount of money the Board has to spend.” Despite the obvious warning in that last phrase, Planters took the bait. As the first group was processed, Perelestrous and Atkinson returned to Russia Nov. 15 for more workers.

The first Russians quickly took jobs and as quickly found reality did not match promises. The Advertiser interviewed complaining workers reporting plantation store prices too high, wages too low, and housing not rent free. Russian and Hawaii government inquiries, with a pro-management interest, concluded problems resulted from workers’ “ignorance …and their childishness” in finance and employment.

In 1910, the second worker group began in grief. Diphtheria broke out in quarantine. Bottled up, bored, hearing stories of real plantation life, they balked. With no photo of the 1910 group, the Advertiser recaptioned the original 1909 photo “Trouble May Result in Deportations.” Most new recruits refused to sign up for jobs even after a pep talk from Russian speaking Samuel I. Johnson, Elks 616 member and Hawaii National Guard head. Saying they’d rather starve than work on plantations, the immigrants exited quarantine April 4th, many of them following the Spaniards to California. As Russian workers dissolved, questions were raised about Perelestrous / Atkinson promises vs. reality. How much Atkinson knew of the promises made is not known.

In 1910 it was back to work: Sugar laborers, just starting a long trudge to unions were exhausted and families hungry, they gave up their strike; Jack Atkinson gave up adventure for work as a private attorney. He too was getting hungry.

Anita Manning, Lodge Historian

References:

Meaning the recruits were not Roman Catholics.

Advertiser 1909 Oct 22, 1910 Mar 3

Atkinson, A. 1915 Mid-Pacific Magazine: “Two Siberian cities,” 9(4):338ff; “Manchu days,” 10(1):56ff

Friend 1909 Nov, p 23, Dec p18; 1910 May p 18

Nordyke, E. C. 1989 The Peopling of Hawaii, UH Press

Kaufman, S. B. ed 1986 The Samuel Gompers Papers, Univ Ill Press, 6: 471-472.

Tabaci, R. 1983 Pau hana. Univ of Hawaii Press

Russian Collection – Passport Application Album

http://libweb.hawaii.edu/libdept/russian/index.html

Thank you to University of Hawaii Librarian Patricia Polansky for access to her research on Russians in Hawaii.